DPDC PRACTICAL GUIDE SERIES | SEDITION

The offence of Sedition in India has taken a controversial shape in the recent past and has increasingly become a cause of concern for journalists. The offence is largely based on the principle that every state must be armed with the power to punish those who challenge the legitimacy of the State Authority by means of words, signs, visible representation or otherwise, which may result in disruption of ‘Public Order’. At the same time, sedition cannot be used as a tool to scuttle the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression, as well as a journalist’s right to practice her profession, guaranteed under the Constitution of India (‘Constitution’).

What constitutes the offence of Sedition?

Section 124A was inserted into the Indian Penal Code in 1870, with the words "hatred" and "contempt" being added along with “disaffection” by an amendment in the year 1898. The provision, as it now stands, states:

Sedition - Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law in India, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine.

Explanation 1 - The expression "disaffection" includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity.

Explanation 2 - Comments expressing disapprobation of the measures of the Government with a view to obtain their alteration by lawful means, without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Explanation 3 - Comments expressing disapprobation of the administrative or other action of the Government without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Is the offence of Sedition as vague and broad as the text of the provision?

The Supreme Court of India in Kedar Nath (AIR 1962 SC 955) found that if read plainly, the provision curtailed the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression in a constitutionally impermissible manner. However, instead of striking down the provision, the Supreme Court narrowed its scope, while upholding its constitutionality. As a result, the offence of sedition only punishes such actions, written or verbal, that are "intended to or has a tendency, to create disorder or disturbance of public peace by resort to violence."

Any attempt to bring a reform in the policies of the Government by lawful means or a fair criticism of its policies is not ‘sedition’.

What is the punishment for sedition?

Section 124-A of IPC contains three distinct kinds of punishments:

● A fine,

● Or imprisonment up to three years and a fine,

● Or imprisonment for life and a fine

Determination of adequacy of punishment (whether fine or imprisonment or both) is within the discretion of the judge, which she must exercise judiciously. The text of the provision offers no guidance on how to differentiate between different cases and decide which kind of punishment is merited by which set of facts. The court, however, is guided by the general guidelines on sentencing laid down by the Supreme Court in its judgements over a course of time. This includes an enquiry into the allegations and evidence brought forth to prove the allegation as well as the numerous mitigating and aggravating factors.

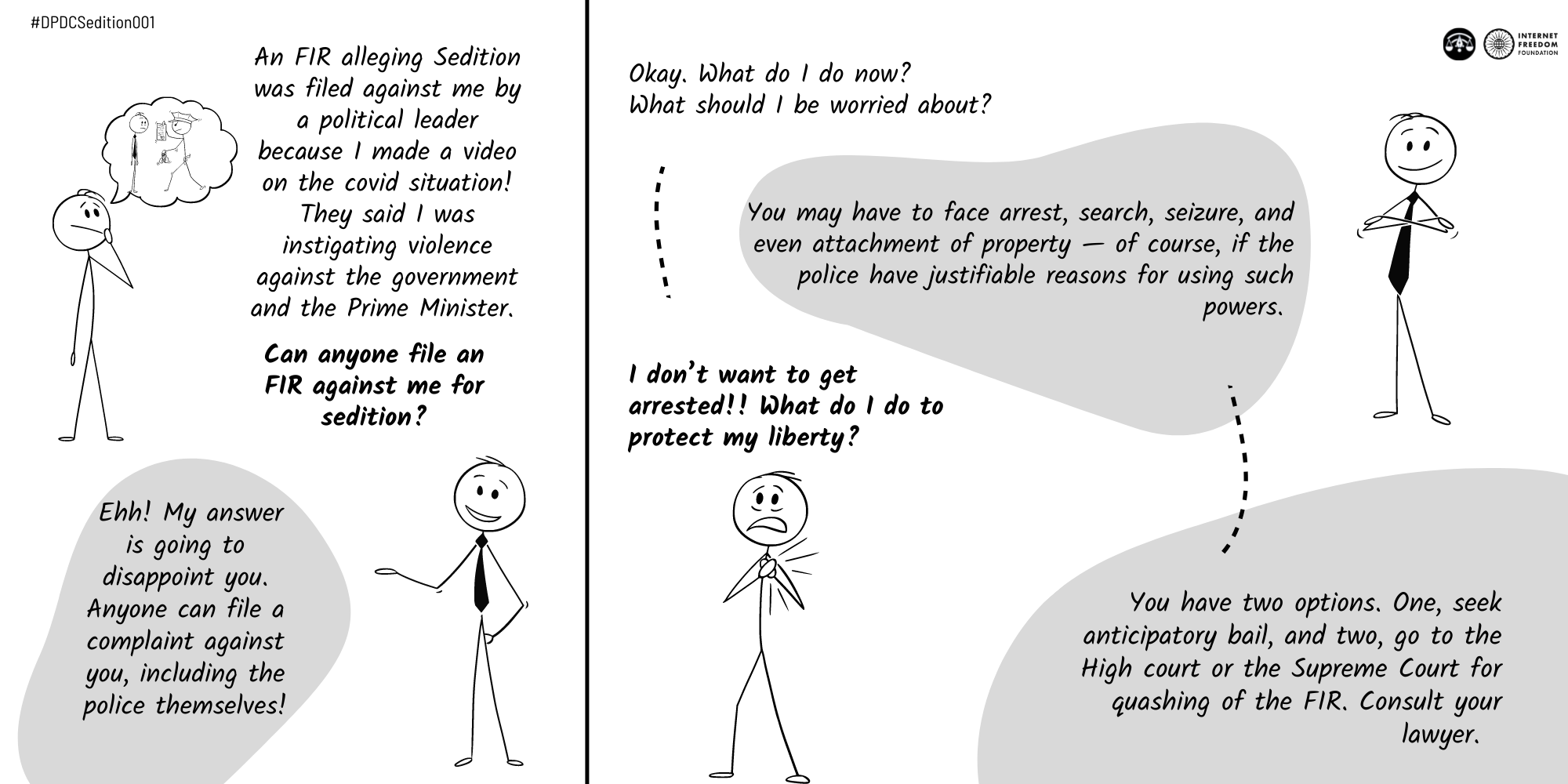

Can anyone accuse me of sedition?

Yes. There is no restriction on who can file a complaint alleging sedition, or on the police investigating this allegation. However, there is a restriction on a court from proceeding ahead with the matter once the investigation is complete (which is discussed later on in this post).

I have just found out that an FIR has been registered against me for the offence of sedition. What should I be worried about?

Sedition is a cognizable, non-bailable and non-compoundable offence which is triable by a Court of Session. This essentially means that the Police can exercise the powers of investigation or arrest without the prior permission of a Magistrate. As a necessary corollary, you may have to face arrest, search, seizure, and even attachment of property — of course, if the police have justifiable reasons for using such powers.

Since the offence of sedition is non-bailable, you have no right to be released on bail upon arrest. Instead, bail may be granted by a court if it finds reasons justifying your release. These reasons are subjective and depend on a case to case basis, but broadly factors such as the possible threat to witnesses and sanctity of investigation, seriousness of allegations, antecedents of the person concerned, and requirement of custody from the standpoint of the investigation are some common factors considered to decide bail.

What can I do to protect my liberty?

If you have reason to believe that you have been accused of sedition—no matter whether an FIR has been registered or not—and you apprehend that the police may arrest you, then one option to proactively protect your liberty is to consider seeking ‘Anticipatory Bail’ under section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 from the concerned court. Remember, anticipatory bail is not to be given for the asking, and going down this road also involves risks. You should speak to a legal professional for advice.

If you think that the accusation is malicious or otherwise false, then you may also consider taking steps to get the FIR quashed and file for a ‘Quashing’ of the FIR itself before the concerned High Court. Such relief is exceptional in nature and can only be granted by a High Court or the Supreme Court of India, where the court must be convinced that the allegations are either baseless, or malicious, or even if taken at their highest they do not make out the alleged offence in law.

You should speak to a legal professional for advice before taking either of the steps.

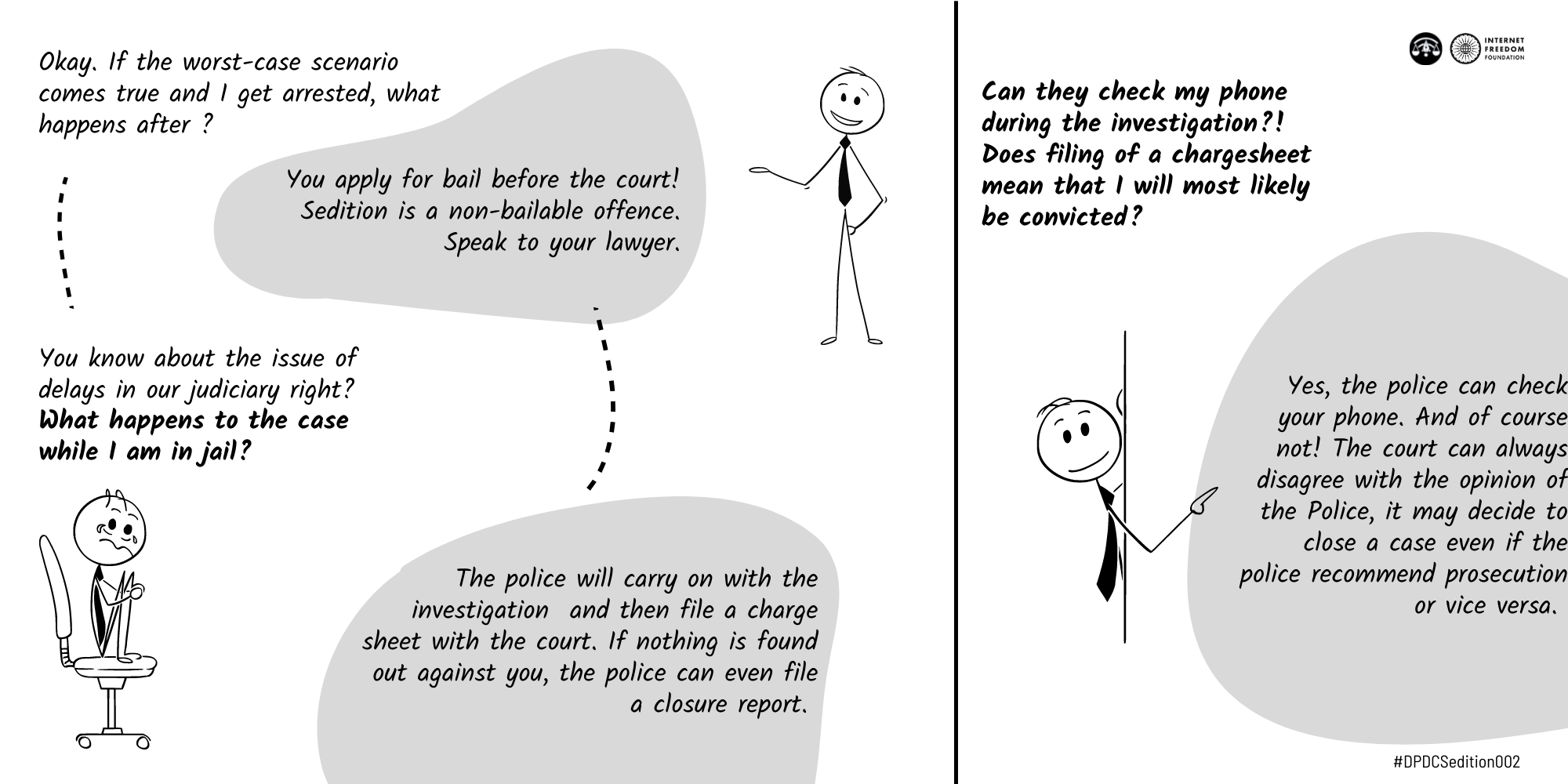

If you are an accused, can the police check your phone during investigation?

Yes. Since police officers have the power to search and seize the mobile phone of any person, with or without a warrant (with recorded reasons in the latter case), they can ask to check your phone. The police may even ask you to surrender your phone. It is quite likely that the material found on your phone may be used against you.

The Karnataka High Court in 2021 has held that an accused person has a duty to cooperate with the investigation and even disclose the password to a mobile phone, but this may not be a correct position of law and is debatable. You should speak to your lawyer to determine the most appropriate course of action.

(A helpful guide on the issue may be accessed here)

What happens if I get arrested?

As a matter of procedure, once you are arrested, the police are duty-bound to inform a next friend about your arrest, inform you of the grounds of arrest, get your medical examination done and produce you before the nearest or concerned Magistrate within 24 hours of arrest.

In the event of an arrest, please seek professional legal assistance to understand the allegations and get advice on next steps. This may include seeking bail by moving an application before the concerned court. Even if a bail application is rejected, you can challenge this rejection before the superior court, going all the way up to the Supreme Court.

A subsequent application can be filed later before the same court, where you must demonstrate what change in circumstances has occurred since the previous bail rejection that a court ought to grant bail this time around.

What happens after the police completes an investigation?

Once the investigation is complete, the police will file a report with the court. It will either recommend that the case be closed (‘Closure Report’) or recommend that you should be tried for the offence (‘Chargesheet’) with or without reserving the right for further investigation. A court will require you to appear once the police files its report, by either issuing summons or warrants for securing your presence.

The court can always disagree with the opinion of the Police, it may decide to close a case even if the police recommend prosecution, or vice versa.

Once you appear in court, you will be supplied with a copy of the police report by the court. Since sedition offences can only be tried by Session Court, the case will be sent to the Sessions Court once the formalities around supply of all documents are complete. This court must decide whether charges should be framed for a trial to proceed, or whether you should be discharged without trial.

Trial itself involves recording of evidence, beginning with the prosecution case where you get a chance to cross-examine the prosecution witnesses. After this, you will be asked to tender a ‘statement’ without oath, and then given an option to lead evidence in your defence. The court hears arguments once evidence concludes, and then decides the case by recording a finding of innocence or guilt. If you are convicted, then sentencing hearings will be conducted.

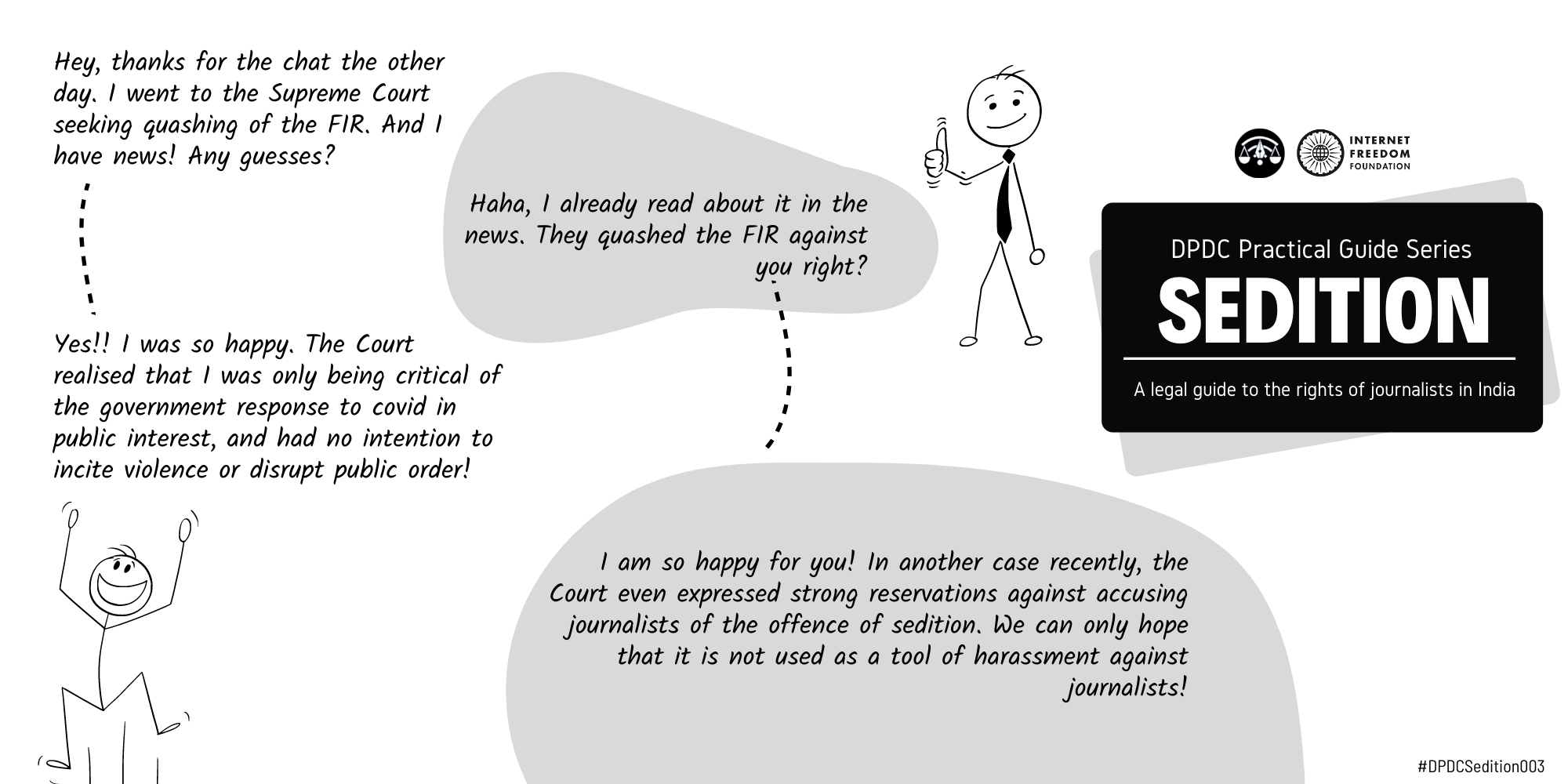

What are the Defence(s) to the offence of Sedition?

When a case of sedition has been registered against a journalist, it is most likely that the explanations to Section 124A may be applicable in protecting the journalistic work. As per the explanation, any comments made in disapprobation of the measures of the government with a view to seek a change will not constitute sedition. The comments, however, cannot be such that they excite hatred, contempt or disaffection. This also covers comments expressing disapprobation of any administrative action of the government.

The explanations were recently considered by the Supreme Court in Vinod Dua v Union of India (Writ Petition (Criminal) No. 154/2020), a case where Senior Journalist Vinod Dua was accused of sedition for his critical comments about the Government and particularly the Prime Minister on the measures adopted by the Government in response to the Covid-19 situation. The Court also specifically mentioned that journalists were entitled to the protection under Kedar Nath Singh. Before this, the Supreme Court, in Aamoda Broadcasting Company v. Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2021) SCC OnLine SC 407 also expressed strong reservations against accusing Journalists of the offence of Sedition.

We hope that this information helps you understand your rights as a journalist reporting in India. The next guide on the series will discuss digital rights of journalists.

DPDC has successfully conducted 33 sessions between Sept 2021 and Mar 2022 and the lawyers were able to provide pro bono legal aid to 29 journalists. If you are a journalist in need of legal aid, fill this form or write to us at [email protected].

This Guide was prepared with assistance from Bharucha and Partners. This blogpost, or any other blogpost published as a part of this practical guide series does not constitute legal advice.